Sprites, Camera, Action!: VN Cinematography in Of Sense and Soul

One element that sets the renewed Of Sense and Soul demo apart from its original iteration is the wealth of camera movement and sprite animation that has been added to the game. Up until December of last year, I hadn’t given much thought to the way the story is told through the “camera”—my focus had been on static images, with a focus on all the variants I wanted to include for things such as sprite expressions and background time changes.

When it came time to bring the images into the game, I had programmers help me create automatic animations for the sprites, including sprite dimming/brightening during dialogue, entrance and exit transitions, and mouth movements for speech. These revealed some issues with the sprite art—the open and closed mouths I had originally drawn were drawn with facial wrinkles to reflect their movements, but when animated these wound up being distracting because they created too much discrepancy between expressions.

This was the consideration that made me begin thinking about Of Sense and Soul in motion: how animated it could be, and what moving elements I would want to translate from real life to the game versus the things I wouldn’t.

This distinction of what I would or wouldn’t bring into the game is one I found quite important. With an emphasis on semi-realism in my game’s art style, there’s a line I have to tread to avoid breaching the uncanny valley of unsettling resemblance to life.

At the end of the day, Of Sense and Soul is a work of fiction, and it has been designed to be demonstratively fictional. The cinematographic approach I landed on reflects this. I aimed not to be “true to life” or to be in perfect perspective at all times, but to follow the story beats as emotions ebbed and flowed.

A note on terminology: For the purposes of this post, I’m using the term “cinematography” to refer to the use of moving images in order to communicate the events and atmosphere of the story. I will also be using “MC”, an abbreviation of “main character,” to refer to the player character, and “NPC” or “Non-player character” to refer to the rest. I will be using “lens” and “camera” to refer to the view that the player (the “viewer) sees.

I've also presented some of these cinematography approaches in my 2023 VN;Conf talk, From Vision to Visuals: Art Direction and Execution for Visual Novels, which you can watch here:

Going with the (Narrative) Flow

Unlike the precise planning that can come with a more conventional filming process, I didn’t storyboard or plan my approach ahead of time—rather, I hopped into the game, booted up Ren’py Action Editor, and went where the story took me. Though it was trial and error at first, I quickly realized there were shots and techniques I used repeatedly at certain key moments.

Close shots of individual sprites were more common during moments of MC introspection, NPC introduction, and in conversations when the character in focus is making a point. Full shots showing the entire room and the full sprites were used when dialogue was more impersonal or when the story called for a feeling of foreignness. Shots of the MCs and NPCs together with them filling the frame were used in longer conversation scenes to add to the intimacy and focus on the dialogue.

Some shots were more mindfully applied, such as dramatic zoom-ins to emphasise outbursts, dutch angle shots on surprised faces, and blurred heartbeat pumping effects accompanying the heartbeat sound effect used in tense moments.

The way that these shots were sequenced and transitioned also changed as I went forward in the narrative—some shots would be moved into over a few seconds, such as pulling the view out to a wider angle, and others would be cut into almost instantly, usually only accompanied by a slow pan across, up, or down the screen to the character in focus. These accentuated the pacing of the scenes by creating varying levels of urgency.

Shots cutting directly from one to the next without panning was more jarring, which helped punctuate argumentative scenes and heavy silences. Shots that switched between speaking characters with a quick panning motion showed a more dynamic back-and-forth, which added dynamicism to bantering or distance to conversations where a disconnect in understanding between the characters was apparent.

Once I had a good idea of how to move the camera and characters around the screen to achieve these effects, I began to experiment with backgrounds and creating depth in a scene using movement on a 3D stage, along the z axis (which goes closer and further from the viewer). Bringing sprites closer to the viewer helped the feeling of closeness between them, and pulling the background in or pushing it away helped signify where the characters were in the space or showed the lack of importance of the outside world to the conversation at hand.

I also found that defocusing the background by blurring, darkening, desaturating, or even hiding it at certain moments helped lend greater intimacy and gravity to certain scenes. I used this in conjunction with pulling the sprite closer to the viewer to create a dolly zoom effect, which was perfect for enhancing emotional intensity when done in less than a second, and for showing a lack of attention or a “pause” in the scene for inner monologue when done over a few seconds.

And, of course, I could show background details and atmosphere using camera placement and closeness!

This helped set the scene for many parts of the story, including CG illustrations.

Sprites, Animated

In addition to camera movements and arranging the characters around the backdrop, the sprites themselves had animations added to them. Animations such as sprites bouncing in excitement or surprise, leaning in to tease or whisper, stretching up and down when laughing, or bowing out of politeness, helped add emphasis to dialogue without needing to move the camera. This not only reduced the fatigue of constant camera movement but also meant dialogue could be further punctuated by sprites’ body language.

What became much more apparent with the addition of camera movements was the advantage of having a comprehensive sprite expression set across the board.

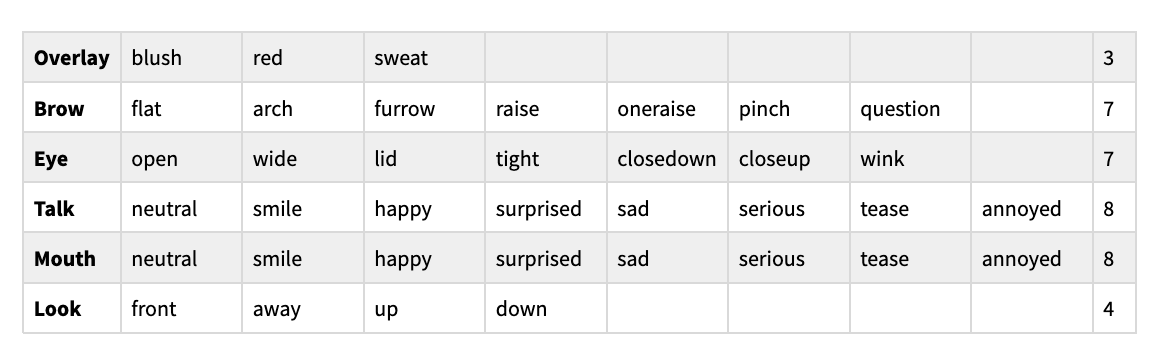

Each Of Sense and Soul character sprite uses 36 distinct images to manipulate facial expressions, encompassing gaze direction, eye shape, brow movement, open and closed mouth positions, and face overlays such as blush and sweat drops.

The wealth of variations that come from having a large set of expressions allowed me to change expressions subtly, reflecting descriptions in the narrative and allowing for changes to take place mid-dialogue.

Characters who lowered their gaze could have not only their gaze move, but also their eyelids follow suit. Characters who were laughing could have their eyes close and arch upwards to show their amusement, and then open again within the same line.

With the addition of closer camera shots and a multitude of ways of presenting sprites, these subtleties became all the clearer: in one scene in Seamus’ chapter 2, only the lower half of Seamus’ face is shown when the camera moves across to him—but his lips purse as James speaks, showing the change in his demeanour before he retorts and the camera pans up to show his frustrated face. A moment later, his widened eyes tighten, then close, as he laments internally that James must know better than to breach the subject of his complicated relationship history.

It’s these minute details that make the cinematography all the more effective.

In traditional motion picture media, an actor’s face can greatly affect the tone of a scene. In a visual novel, there’s less opportunity for those subtle changes—but maximising how sprites’ static faces can change by manipulating individual facial features has increased the liveliness of our characters—even if most of them can’t even change poses yet.

Takeaways

No matter what story you're telling or what engine you're using, cinematography is an extremely powerful storytelling tool that you can use in your visual novels to make an even better playing experience!

- Full-body sprite animations can add liveliness by changing the body language of the sprite.

- Manipulating individual expression components can create subtle facial acting and enhance emotional storytelling.

- Intimacy can be enhanced or reduced by how close or far the lens is to the scene occurring.

- Pacing can be made more urgent or leisurely by changing the suddenness of how scenes change.

- Privacy and emphasis can be adjusted by changing the depth and clarity of the lens, calling the foreground elements to attention while defocusing the background ones.

Thank you for reading this, I hope you found it helpful!

by Ingrid (ingthing), Lead Developer and Artist at Forsythia Productions

To see the cinematography and sprites in action, play the Of Sense and Soul Extended Demo available here on itch.io or on Steam!

Further Resources

- Ren’py Action Editor 3 by Kyouryuukunn is the tool that made this all possible!

- Visual Novel Design’s video on Ren’py Action Editor and video on Leveling Up Sprites helped inspire me to give more in depth cinematography in Ren’py a shot.

- The Ren’py Documentation’s section on Warpers in the Animation and Transformation Language page

Get Of Sense and Soul

Of Sense and Soul

A Slow Burn Queer Victorian Romance VN

| Status | In development |

| Authors | Forsythia Productions, ingthing |

| Genre | Visual Novel, Interactive Fiction |

| Tags | Bara, Boys' Love, Dating Sim, Gay, Historical, LGBT, Period Piece, Romance, Victorian |

| Languages | English |

| Accessibility | High-contrast |

More posts

- Ext. Demo Ver 4.1 (Big Bug Fix!) + 4.2 (Little Bug Fix)Nov 27, 2024

- Ext. Demo Ver 4.0 + Season of Pride 2024!Nov 25, 2024

- OSAS broadcasting for The Storyteller's Festival 2024 on Steam!Jan 31, 2024

- OSAS Dev Update: September-October 2023Nov 01, 2023

- In Memory of Mateo ErvinOct 16, 2023

- OSAS Dev Update: July-August 2023Aug 23, 2023

- 103% Funded! A Voiced CG Preview & Next StepsAug 17, 2023

- Ext. Demo Ver 3.0 + Kickstarter CountdownAug 04, 2023

- Halfway Through! Kickstarter Week 2 Progress, Plot Thickening, and FanartJul 27, 2023

- KS Milestone Rewards: New Demo Content & A Voiced Preview!Jul 17, 2023

Comments

Log in with itch.io to leave a comment.

As someone who studied film, I'm honestly super interested in how to bring a more cinematic feel to VNs and this post opened my eyes to a new world of posibilities!